So you’re a member of a horde of trillions of hungry migratory grasshopper nymphs (aka hoppers) looking for a place to live large. Do I ever have the place for you: eastern Wyoming, where it’s been a Goldilocks year for grasshoppers.

So you’re a member of a horde of trillions of hungry migratory grasshopper nymphs (aka hoppers) looking for a place to live large. Do I ever have the place for you: eastern Wyoming, where it’s been a Goldilocks year for grasshoppers.

Even as I write, a hungry, hungry swarm of one of America’s legendary scourges is crunching and munching and chewing up hay, wheat, and alfalfa fields in that part of the country. Airborne sprayers dispensing moult-disrupting chemicals are currently getting slimed every time they fly with a film of grasshopper goo. In a normal year, one sprayer said he might tackle 2,000 acres. This year he is looking at flying one million.

Americans have, I think, a particular trauma about these insects, which may be part of our national aversion to insects in general, a topic I’ll shortly be exploring in a guest post over at the Beetle Queen blog, where I’ve kindly been invited to guest-blog. For now, let’s just say we and grasshoppers have had issues.

Grasshoppers belong to the Orthoptera (Look for and explore them here), an order of insects that also includes the katydids and crickets. The notorious “Mormon crickets” that legendarily nearly wiped out the Mormons’ first crop (they attribute their deliverance to the miraculous intervention of California gulls, which are even now the state bird) in Utah were actually katydids, but still in this order. The members of Orthoptera have enlarged hind legs (the better to hop with), well-developed compound eyes (the better to see you with), and very efficient mandibles (the better to annihilate crops with).

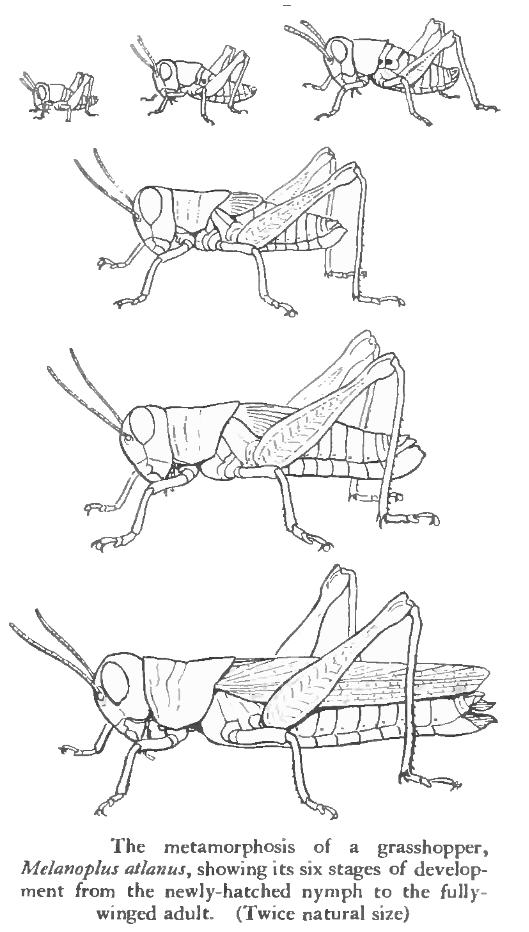

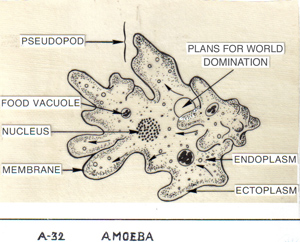

You may think of insects as always developing from squelchy, soft-bodied larval young, but it turns out this is not the case. Many insects, including grasshoppers, use an alternative system involving nymphs, pint-sized (pea sized?) versions of adults. No maggots necessary.

The insects that do this are called hemimetabolous, which means something like partially metamorphic. This distinguishes them from the ancestral form, called ametabolous (“not metamorphic”), found in silverfish (fun fact: one alternate name is “carpet sharks”), bristletails, and other less-derived (aka primitive) insects in which the animal just keeps moulting and growing its whole life, and holometabolous insects like butterflies, in which there is an Extreme Makeover: Insect Edition that usually involves some sort of hideous larva and walled-off pupa.

Hemimetabolous insects like grasshoppers, cockroaches, mantids, true bugs, dragonflies, damselflies, mayflies and stoneflies* hatch looking more or less like their elders.

That’s not to say there’s *no* difference between nymphs and adults. Notice anything odd about this picture?

Look at the wings — they’re just little flaps. In fact, in grasshopper nymphs, the little flaps have an even stranger behavior. They go from right-side-up to upside-down and back again. Or actually, upside down to right-side-up and back, since the part of the wing with the thickest vein (like the front edge of a fly’s wing) is actually on their stomach side in the adults. Yes, that’s right. They’re flip-flopper hoppers. In the above photo, the wings are in their intermediate position.

Other nymphs undergo sometimes significant changes in color and shape, but the overall form remains the same. The different juvenile stages of insects, whether larval or nymphal, are beautifully called instars (Instar, by the way, is one of my cellar doors).

The reason I mention all this is that the plane-sliming swarms of grasshoppers currently occupying Wyoming were, as of a week and a half ago, still only tiny nymphs. From the NYT:

On Wednesday afternoon, Ms. Mahnke from the county Weed and Pest office drove out to one particular hatching ground that she said was without equal. In recent days, she said she easily counted 40 to 50 or more tiny grasshoppers, many still the size of a grain of rice, per square yard. If multiplied across five million affected acres, they would yield a trillion insects or more.

Walking through the calf-high grass in such a field feels like something out of primordial biology 101. Every step stirs a tiny, nervous crowd, jumping every which direction — up, down, away and onto one’s pants. Adult size in such numbers, vastly larger, jumping and flying — and by the adult phase, eating in volume — would do Alfred Hitchcock’s best nightmare one better in a dozen paces.

Stay tuned.

__________________________________________________________________________

*Nymphal aquatic insects are, for historic and confoundingly confusing reasons, referred to as larvae even though they are technically nymphs. Or, just to make things more confusing, they’re sometimes called naiads, a holdover from the days all biologists (and really, all students), had to master Latin, Greek, and the classics. Is it naughty of me to sometimes wish for those days?

{ 1 trackback }

{ 0 comments… add one now }