We are no longer the only phylum to discover these leaves are crazy delicious. Creative Commons paul goyette

It’s 1875. You’re a French winemaker. Your vineyards have only recently recovered from the trauma of grafting every single vine to American grape rootstock to avoid the plague of the accidentally-introduced American Phylloxera aphid, which nearly wiped out Europe’s wine industry in the Great French Wine Blight. And now, your vines are withering once more. The leaves are yellowing, the grapes and shoots are wrinkled or distorted, and covering everything is a white, downy fuzz. Congratulations: You’ve just acquired grape downy mildew, Plasmopara viticola, also recently accidentally-introduced from America, and 50 to 75 percent of your crop could be gone in a single season. Sacré bleu!

Several years would pass before the French botany professor Pierre-Marie-Alexis Millardet would walk by a vineyard in France’s renowned Medoc region of Bordeaux and notice a funny thing: the grapes next to the road looked much better than the grapes farther afield. What was up with that?

Now personally, I think that would have been perfect fodder for dial-in to Grape Talk, the 19th Century public radio show about grapes and grape repair. But Professor Millardet did the next best thing: he asked the locals what might be going on. And as it turned out, the growers were spattering their roadside vines with a visibile, poisonous substance like verdigris to deter hungry passersby from sampling their product. Inspired, Millardet went home, got out the chemistry set, played around, and in 1885, cooked up a solution of copper sulfate and calcium hydroxide(quick lime) that he thought worked best. Thus was born Bordeaux Mixture, the world’s first fungicide. France’s grapes were once again saved.

Fast forward to 2010. You’re a vegetable farmer in New York. You have only recently recovered from the 2009 trauma of dealing with late blight spread by big-box-store marketed tomatoes to home growers all over the east. And now, your entire basil crop is yellowing and spotty. Since consumers will not accept leaves with any blemish, it will be a total crop failure. Congratulations: You’ve just acquired the newest downy mildew epidemic to strike the world: basil blight, Peronospora belbahrii. Holy @%$*!

As reported by NPR this week and pointed out by alert reader kati, basil downy mildew is taking the east by storm. And by now you must be wondering, “Just what is this downy mildew stuff?” Good question. Because, in spite of its mildew moniker, it is not a fungus. Or at least not a fungus in the Fungus sense of the word. Lemme ‘splain.

In the ocean there are many things that swim and have fins. But not all are fish. Fish are only distantly related to whales and dolphins. But when the ancestors of whales and dolphins put out to sea, natural selection shaped them into a form quite similar to fish, who had the good sense to stay put all along and not mess around with that highfalutin’ land stuff. We call this convergent evolution.

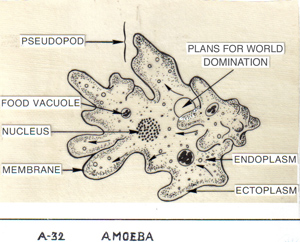

In the case of what we call “fungi”, there are two distantly related groups who have evolved to look a lot alike. On the one hand, the true (capital-F) Fungi. On the other hand, we have the Oomycetes (oh-oh-MY-seats), or water molds, who may look like fungi and may be called (little-f) fungi, but decidedly are not taxonomically.

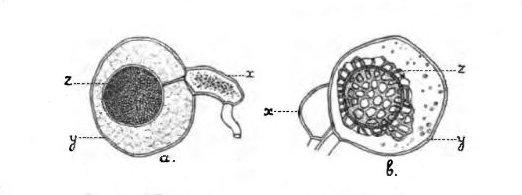

If these were humans, this would be censored. Oomycete sex: the large round oogonium containing the female gamete (egg) is fertilized by the smaller male "antheridium" borne on a separate filament or "hypha".

The funny name provides a clue to how oomycetes differ from true fungi: during sexual reproduction, they make egg-like structures called oogonia, which are fertilized by male structures called antheridia to form oospores. This is but one difference. There are others.

Oomycetes are heterokonts (aka stramenopiles, like brown algae and diatoms . . . remember?) which mean they have two kinds of flagella(propeller tails) for their swimming spores (zoospores). One is called the tinsel: it’s hairy and points forward. The other, the whiplash, points backward and is smooth. Both flagella are attached to the same point on the side of the zoospores, not the front or back.(The only true Fungi that possess flagella, the chytridiomycetes, have only a single, backward-directed flagellum)

Second, the cell walls of oomycetes contain, among other things, cellulose-like material (cellulose also being one of the major components of the cell walls of plants), unlike true fungi, which have chitin in their cell walls (the same stuff insects and crustaceans use to harden their shells). Interesting how the same molecules keep popping up all over life on Earth, isn’t it? It is likely that they evolved independently in all these groups, too. Kinda makes you think!

Finally, most fungi are haploid (contain only one copy of the blueprints) for most of their life. Oomycetes, on the other hand, are more like us: almost as soon as they make their gametes, they fuse them to restore two copies of their chromosomes to their cells.

Oomycetes can be (and often are) called fungi (lowercase f) if it is used as a common name, since they seem to have independently evolved into the same niche as fungi, (filamentous moisture-loving decayers and parasites), the same way that birds and bats, whales and fish, and cacti of America and Euphorbia of Africa have. Still, you wouldn’t call a whale a fish or a bat a bird. : )

Downy mildews are a sub-group within the oomycetes composed of the family Peronosporaceae. They have specialized on parasitizing higher plants. They make special highly developed branched sporangiophores (sporangium bearers) to hold their sporangia (See Fig. 7 here), or cells inside which spores develop. The sporangia make asexual spores, which in many downy mildews can be the zoospores with the tinsel and whiplash flagella that need water to get around. But in Peronospora, the genus killing our friendly basil plants, the sporangium just sends out a hypha (filament) to germinate, just like most true fungi, and calls it good.

What’s more, their sporangia are windborne, and can be blown from plant to plant without need of water. When combined with dense crop monocultures, this is a recipe for destruction, much as it was when early blight of potato (another oomycete but not another downy mildew) arrived in Ireland in the 1840s.

So where did our spunky new downy mildew come from? No one knows. Basil downy mildew was only reported once before the 21st century in Uganda in 1933. So this may be a mutation of a strain from Uganda, or it may be a species that evolved totally independently elsewhere. According to Margaret McGrath at my old Plant Pathology department at Cornell, the first report of this particular species was in Switzerland in 2001. From there it spread across Europe and thence came to Florida in October 2007. It has also spread (back?) to Asia and Africa. And it looks to be here to stay.

Like many fungi, this is a nasty parasite that can be almost impossible to rid yourself of once acquired, short of heavy fungicide application, which most people do not want to do to basil plants they plan to be eating. Cornell’s Margaret McGrath has only one piece of advice for the first time you find it on your basil: make pesto NOW.

To see how the heterokonts (aka stramenopiles) fit in to the rest of the eukaryotes (cells with nuclei), go here. Then click stramenopiles to find the oomycetes among the diatoms, brown algae, and other weird, obscure creatures.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

definitely weird and wonderful (except to the basil) and blowing my mind :) thank you!