Arthropods! The prolific joint-legged and exoskeletoned group is up there with bacteria, archaea, and nematodes in the relentless numerical domination of Earth’s surface. Here is a picture of me with one taken this week:

It’s a whip scorpion, in the order Thelyphonida, although this one has sadly somehow lost its long thin tail, or “whip” (called technically, like those of protists and sperm, a flagellum — but they are *not* evolutionarily-related structures). This one seems to be very well fed, though thankfully not on Jen. I’m taking a short arachnology class at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science right now, and this was one of our subjects. According to my classmate, these animals, also commonly called vinegarroons because of the defensive acetic acid (vinegar) glands they possess near their tails, are the nerds of the arachnid world: “They just kind of bumble along, smelling like a salad.” Raptoral pedipalps (big scary pincers) aside, the one I held did seem to be a sweet, gentle creature. I’ve now held a whip scorpion! Yay!

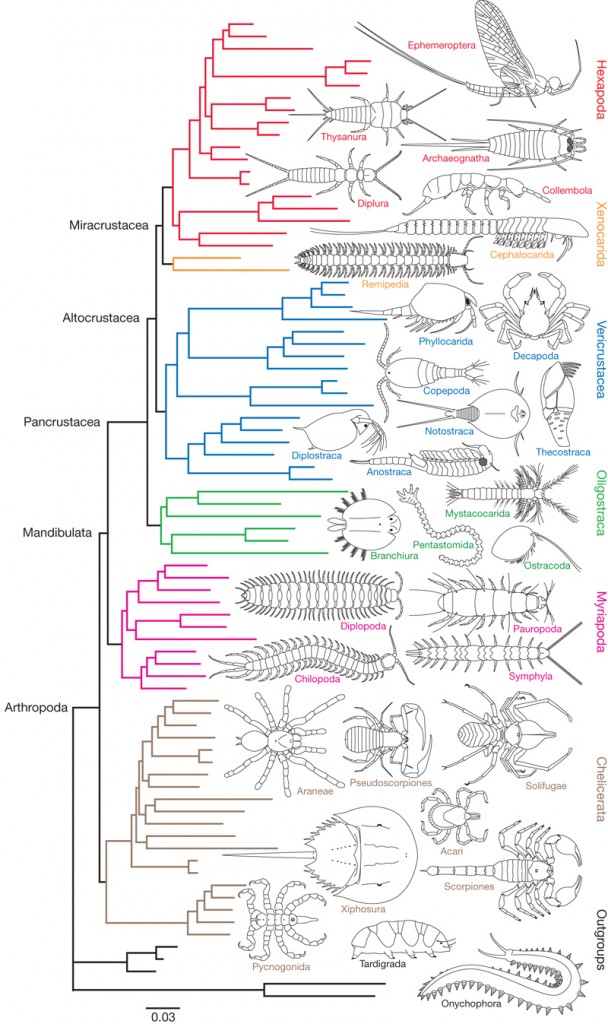

I haven’t talked about arthropods at this blog much yet, and a paper published in Nature a few weeks ago together with my play date with Stumpy, above, provide the perfect opportunity to correct that. This post is called “The Creepy-Crawly Branch of the Family Tree”, but it could equally well be called the Floaty-Swimmy Branch, or the Bloody-Sucky Branch or the Borey-Eggs-Iny-that-Hatchy-and-Devour-the-Insides-of-your-Hosty Branch. There are arthropods that do all these things. So let’s have a look at the broad shape of the tree as revealed by this new analysis of the evolutionary relationships among members of Arthropoda:

Arthropod relationships revealed by phylogenomic analysis of nuclear protein-coding sequences Jerome C. Regier, Jeffrey W. Shultz, Andreas Zwick, April Hussey, Bernard Ball, Regina Wetzer, Joel W. Martin & Clifford W. Cunningham Nature 463, 1079-1083(25 February 2010) doi:10.1038/nature08742

Now there are a lot of scary words on this diagram, it’s true. But take heart! Look how many drawings of awesome creatures there are! And it’s way better than the alternative that most biologists have to deal with, which I also had to learn to read in school. Before I get to what’s new and cool about this tree, let’s talk a little bit about what trees like this are, and then about the main groups you see on it.

This tree is called a phylogeny, or phylogram (you also hear cladogram). It is a hypothesis of evolutionary history. That doesn’t mean scientists are hypothesizing that these creatures evolved. That’s a foregone conclusion. The hypothesis is what the specific relationships are between the different groups. In other words, the question is, “How is everyone related?”, and this tree is one possible answer. In some trees, as appears to be the case here, the branch lengths are proportional to the evolutionary distance between the different groups. That is, the longer the branches, the more evolvin’ that’s been going on. Evolution, in this case, is measured in DNA nucleotide changes. DNA, as you’ll recall, is made of many base pairs called nucleotides. There are four kinds. When one changes to another, that is called a point mutation. The more of these changes that build up, the greater the evolutionary distance between groups.

For this tree, scientists studied 62 genes in 75 arthropod species. They sequenced them all and compared the changes. They put all the data into a special computer program designed to figure out which sequences are most similar to which other sequences in the five-jillion possible combinations of relationships embodied by 62 genes in 75 species. Then they cranked the computers up to 11 and probably waited a few days (or maybe even weeks! I have heard stories of scientists locking computers in closets during this time) for them to churn out the solution to this hyper-space chess problem. The lone tree you see above is the result.

So what do we see? At the top is Hexapoda, which as you may guess are insects and friends — the six-legged among us. Below them you see an interesting group called Xenocarida. More on them later. Below that group are the Vericrustacea and Oligostraca, which are both, as far as I can tell, basically crustaceans. In both groups you see some old friends: the copepods (some freshwater species of which carry Guinea Worm larvae, a topic I covered in January), the ostracods (who we looked at in a post on deep-sea bioluminscent organisms last year), and the Decapoda, which has a high taxonomic tastiness index: it includes lobsters, crayfish, crabs, and shrimp.

Next are the myriapods: centipedes and millipedes. Below that are the chelicerates, or organisms with special mouthparts called chelicerae — sea spiders (pynogonids), horseshoe crabs, scorpions, ticks, mites, tarantulas, spiders, and Stumpy. And rounding out the base of the tree are the outgroups — the groups we use to “root” the tree, or give it a direction. They are usually the most closely related organisms not in the group of interest, here arthropods. In this case, they are the ridiculously cutely-named water bears or moss piglets — the tardigrades — and velvet worms, the onychophorans. Velvet worms are half of the subject of a crazy-*** theory that somehow got published last year hypothesizing that metamorphosing insects like butterflies were the result of an unholy chimerical union between velvet worms and a larva-less insect.

Also looming large in the arthropods but not on the tree simply for reasons of chronological discrimination (and also because, being extinct, we have no DNA to sample) are the the trilobites. According to my copy of Colin Tudge’s Variety of Life, they branched off somewhere between the Tardigrades and Chelicerates.

OK, so now that you’ve waded through all of that, what were the surprises in this new tree? Scientists also used to think millipedes and centipedes were closely related to insects. They’re both land arthropods, after all. My two college biology texts (published 1995 and 1996) show this relationship, though Tudge(2000) is agnostic on whether millipedes and centipedes or crustaceans are more closely related to Insects. Now it appears certain that, since all crustaceans are aquatic, insects and centipedes/millipedes represent a seperate evolutionary invasion of land by arthropods, much as seals and whales represent two seperate re-invasions of the sea by mammals.

This study also supports the hypothesis that insects evolved from a crustacean, which is why we can’t use the term “Crustacea” any more — the group as traditonally defined doesn’t include the insects, but this tree shows that it should (since the principles of modern evolution-based taxonomy require proper groups to include an ancestor and ALL of its descendants). The term “Reptiles” poses the same dilemma, because it should technically include birds. So some scientists have stopped using that term as a taxonomic classification, too. Little-r reptiles is OK, though, as informal name for the group.

Finally, it appears hexapods’ (insects’) closest relatives are an obscure underwater-cave-dwelling group newly dubbed the Xenocarida. Carl Zimmer goes into that in admirable detail here.

But the take-home message of this tree for you is simple: look, admire, and marvel at the variety and abundance. In fact, I give you a homework assignment, should you choose to accept it: pick a group on that tree that looks interesting that you’ve never heard of before. Look it up. Find out what it is, what it does for a living, and where it directs its mail. You’ll be glad you did, I promise.

{ 1 trackback }

{ 0 comments… add one now }