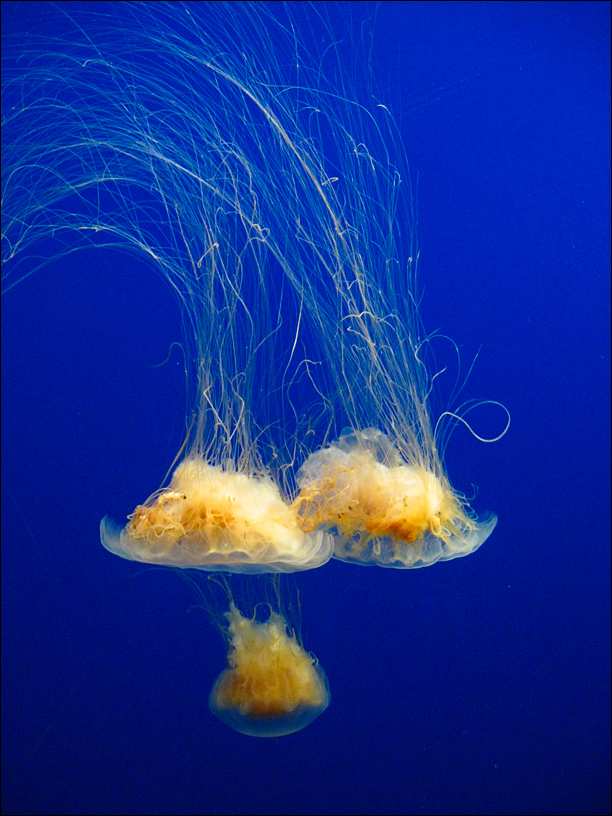

Fig. 1 Young lion's mane jellyfish. You can see how this might be a problem should a big one kick the bucket near a beach filled with wee ones. Creative Commons jadeilyn

Mayhem. That’s what happened this week when a 40-lb. dead member of the world’s largest species of jelly, Cyanea capillata (literally “blue hairs”, I think), washed up near a New Hampshire beach, and zillions of tiny, nearly invisible fragments of its tentacles fanned out through the water like the evil plan of some very-small-scale Bond villain. 150 people were stung. Five ambulances and a hook and ladder truck showed up. Lifeguards were sent to raid local stores for baking soda and vinegar.

In the understatement of the week, one expert had this to say:

“When you’re talking about thousands of tentacles and little kids splashing about, it’s a recipe for chaos,” Professor Harris said.

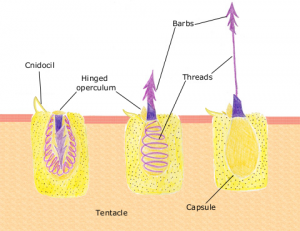

Fig. 2 The business end of a jellyfish tentacle. When the little trigger on the upper left is tripped, the operculum (lid) flips back and the nematocyst, or stinger, flips inside out and is propelled by pressure into fish, plankton, stray toddlers, etc.

Scientists said it was no stunner the kids got stung once the jelly entered the bay. Jellyfish tentacles envenomate victims with famous (to biologists) stinging cells called nematocytes that evert a tiny syringe (a nematocyst) when you touch them. They’re like tiny harpoons with hairpin triggers. These cells can remain alive long after the jellyfish does since they rely on seawater, not the rest of the jellyfish, for many of their survival needs.

What really makes the lion’s mane nasty is what you can observe in Fig. 1, over yonder above left: eight clusters of up to 100 gossamer tentacles each. These are young specimens, when they get old and purple, they have enough tentacles to make a New-York ticker tape parade look like a light sprinkle of streamers by comparison. And did I mention the tentacles grow up to 120 feet long? That’s longer than a blue whale.The bell that accompanies 120-foot long tentacles can reach eight feet across. That’s three feet across longer than me. I’m sure the tentacles easily break into tiny, irritatingly noxious and barely visible pieces once the jellyfish bites the big one.

Lion’s mane jellies are found in the cold, northern oceans of the world where it feeds on fish, comb jellies, moon jellies, small crustaceans, and plankton. It was unusual for this to be so far south, according to experts in the NYT article. It brought to my mind the periodic population explosions of monster Nomura’s jellyfish giving Japanese fisherman no end of aggravation, in one case even capsizing a trawler. Jellyfish, people. Jellyfish.

The Telegraph article I’ve linked to here dryly notes the recent periodic explosion in Nomura’s population may be do to fewer predators like sea turtles and fish in the area. Let’s see . . . perhaps because of overfishing? Indeed, jelly populations have been climbing world-round, causing all sorts of headaches. There’s lots of speculation about why, and Smithsonian Magazine even devoted and entire article to it in their recent 40th anniversary edition, but it probably comes down to two things: We’ve caught and eaten many of the other fish that would normally compete with them for food, and the oceans are getting warmer and more acidic, which bothers many things but apparently not jellies. Don’t forget your Monterey Bay Aquarium (or equivalent for other continents) Seafood Wallet Watch Card or iPhone app next time you’re buying seafood.

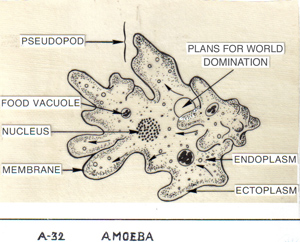

Lion’s mane jellyfish are true jellies in the phylum Cnidaria (That’s a silent C — Nigh-DARE-ee-uh), a major group of animals that was probably the second group to split off the main animal line after sponges, the Porifera. You can see the broad outline here in this easy-to-understand tree. Though the jellyfish may indeed be beating out my favorites, the slime molds, with their world-domination plans, I don’t love them less. The true jellies are in one group of Cnidaria called the Scyphozoa, but they have all sorts of weird and wonderful relatives like all corals, sea pens, sea anemones, and box jellies containing some of my favorite beautiful organisms on the planet. When I go to aquariums, phylum Cnidaria is the one that mesmerizes me most often. Rest assured, you’ll hear more about them here.

{ 2 trackbacks }

{ 7 comments… read them below or add one }

Lion’s Manes are nasty enough to have nearly killed Sherlock Holmes, too.

Nearly.

At the other end of the “size” spectrum, another clear sign of jellyfish world-domination plans: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irukandji_jellyfish

Isn’t the “Dunwich Horror” set close to New Hampshire? Perhaps it isn’t too late

to start worshiping Cthulu or the other Old Ones. Doom is imminent :-).

Ah, yes. The Australian box jellies — among the most venomous creatures on Earth. Living proof that it’s not the size of the bell, it’s the motion in the nematocyst.

thought of you!

http://www.cnn.com/2010/WORLD/americas/07/26/eco.oldest.living.things/index.html?hpt=C1

Very cool! Will do a quick post on that soon. Thanks for the link! My fave is the green rock. Had not seen that plant before.

Wow! Wow! and WOW! I can’t believe that guy stung his son! I love the idea of thinking about creatures based on their age. So many times, I wonder how old a certain animal or plant appearing in a nature show is. And a beach full of jellyfish stung adults and children… Yikes!

I used to think that they are deadly. thanks for the informative article. your blog seems very interesting. will be coming back for more.

thanks a lot.