A few weeks ago I was graciously allowed to accompany local lichen expert Ann Henson on one of her field trips. It was a cold, cloudy, and rainy day at about 8000 feet in Colorado’s Front Range, and by the end I was chilled through. I didn’t care. I learned loads from Ann and took lots of photos. Today, I bring you a fun slideshow of a few of the things we discovered on the trip.

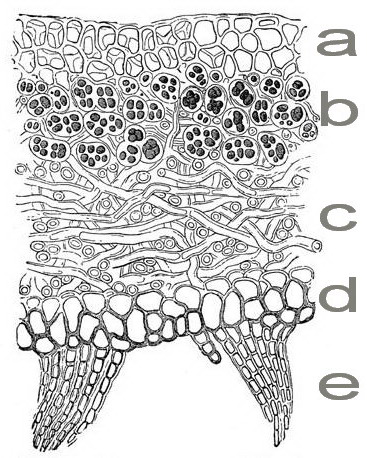

First, a refresher. Lichens are fungus/algal collectives in which it may be a partnership or may be something more sinister on the part of the fungus. The algae are trapped in tangles of fungal filaments and sandwiched between two protective cortices (sing. cortex). To whit:

A and D are the upper and lower cortices. B is the algal layer. C is the medulla. And E are the root-like structures called rhizines. For you botanists out there, this should remind you of something — the cross section of a leaf. Convergent evolution in action again, my friends.

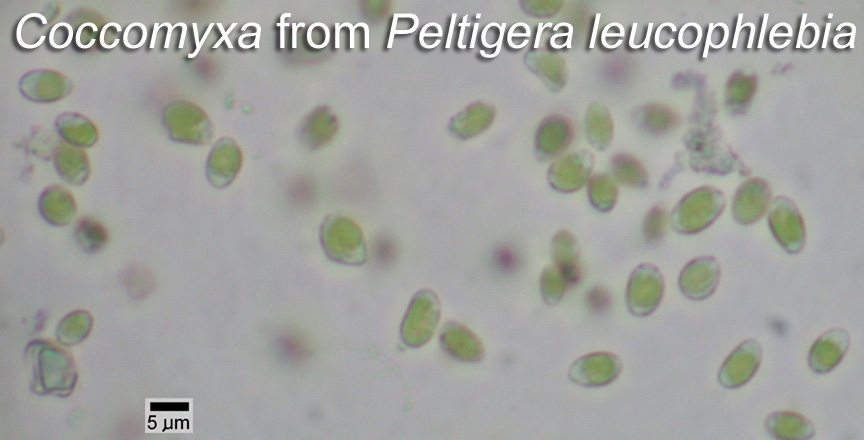

The algae photosynthesize and make the food. The fungus provides a place to live that protects the algae from death by dryness and sometimes provides sunscreen. Though “lichen usually” means one fungus and one alga (conservatives would be happy), it sometimes means one fungus and a few algae (not so happy). The following is one such case.

Here we have the common freckle pelt, Peltigera apthosa. These things can range from bright green when they’re wet to greyish brown when dry and sad. In most of the lichen, the green eukaryotic (nucleated) algae Coccomyxa

holds sway, but the second spouse photosymbiont Nostoc

gets its own little house (the freckles on the freckle pelt in the photo above, also called cephalodia) because apparently partner 1 and partner 2 don’t play nicely together. Notice the bigger cells in the chains of the cyanobacterium Nostoc. Those are called heterocysts and those particular cells can do something most living things cannot: fix nitrogen. Something like 70% of the air you breathe is nitrogen (N2) but turning it into a form living things can use (like NH4, ammonia) is difficult.

Thus nitrogen is a limiting nutrient in most biological systems, and creatures that can make it get extra street cred and often special cushy living arrangements. The nitrogen-fixing bacteria that live with legumes are one such case (thus the invention of crop rotation to keep fields fertile), and so can Nostoc. Hence the quirky living arrangements in Peltigera. If someone made a TV show about this thing, it would have to be called “Big Lichen”. When reached for comment, Coccomyxa admitted the relationship was strange but said it was sometimes fun to sneak out for algae-nights-out with Nostoc and that having more than one alga in the relationship really helped relieve the pressure to put out glucose. But I digress.

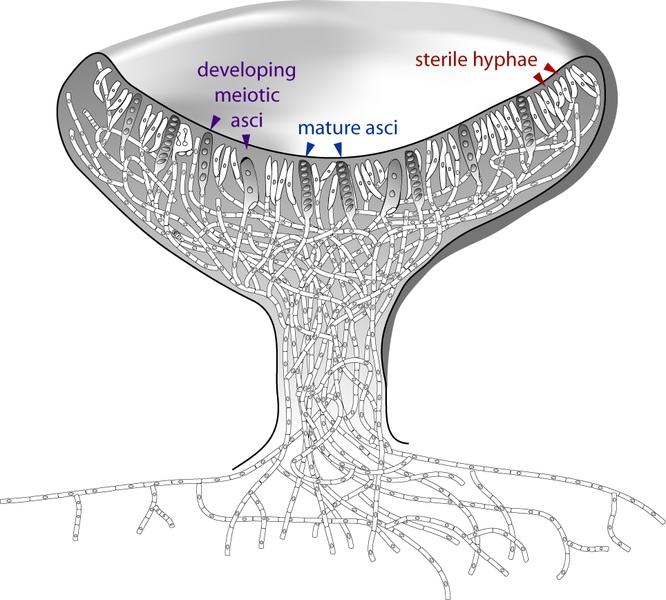

The reddish-brown curvy things on the common freckle pelt are the apothecia, or disc-like reproductive strucutres of the fungus. This is where the fungus half of the lichen gets busy, making its ascopores (sexual spores) in sac-like structures called asci (ass-eye). Here’s a cross section of one in an un-lichenized cup fungus:

So these little cups, or apothecia, are a visible demonstration that a fungus is part of the lichen mix.

Here’s our next subject:

This is Leprocaulon — the “cottonthread lichens” –– either Leprocaulon gracilescens or Leprocaulon subalbicans, probably the former. I had never seen this lichen before in my life and it was an odd one. Ann described it as being “barely lichenized”, and it is a collecting of threadlike granular fibers that stand up from the surface they’re growing on by a centimeter or so. It’s soft. Really soft. The upright fibers move back and forth easily, and when I gave it a pet it was not unlike touching dryer lint. Not like the typical crusty, papery, or fibery lichen at all.

The next two lichens got me really excited.

These dark patches are jelly lichens, and they are what happens when Nostoc rules the roost. I’m not sure of the genus, but it may be Collema or Leptogium. Their fungi are monogamously lichenized to cyanobacteria, and this gelatinous, brown mass is the result. True to their name, they were rubbery and fun to squish gently between the fingers. Interestingly, when Nostoc makes giant colonies of itself on its own, it doesn’t look much different.

So I guess we know who’s wearing the pants in this relationship.

Next we have what Ann called the most spectacular lichen in Colorado, and I agree. To give you a sense of scale, I could easily sit on the rock in the center of this photo.

This is rock tripe, also called Umbilicaria americana. It is unique to our hemisphere. Generally speaking, when the rock looks like its gotten a really bad sunburn and is sloughing its skin, that’s rock tripe. I think it’s called tripe because it was what one could eat when there was nothing better left. True to its generic name, it is an umbilicate lichen. You had an umbilicus once too; it attached you to your mother. Umbilicaria keeps its umbilicus thorughout life. It attaches it to its substrate — in this case, a rock. Look carefully at the photo below. This Umbilicaria is about three or four inches across, or more than 15 cm. The white raised portion overlies the umbilicus underneath.

You probably wouldn’t guess it from looking, but the underside is pitch black and fuzzy.

And, of course, something has found a way to rain on even Umbilicaria‘s parade.

It’s another lichen growing on top of it. This reminds me of one of my favorite lines from Jurassic Park: “Life finds a way.” (although obviously, not always, or we wouldn’t be facing an extinction crisis of staggering proportions that makes me feel both blindingly angry and supremely helpless).

Speaking of de-motivational events, on our way out, we saw this:

Yes, those are two giant sets of bear claw scratch marks on that tree. Though bears aren’t known to eat lichens, I believe they are known to eat hikers. Time to go find some hot chocolate . . .

{ 1 trackback }

{ 3 comments… read them below or add one }

next time take me with you!!! :)

that tripe is fascinating, it does look a little like what you find in your pho soup :)

i am going to get my kids some sorel boots and we are so going to go on a lichen hunt in the cascades one of these days. it’s a must! with some bear spray and a dog, obviously…

Come to Colorado sometime and I will! Definitely take the kids — but also make sure you take a 10x hand lens or loupe. Lichens are even more fascinating under a little magnification . . . your kids will love it, I promise. : )

A fascinating and kind of hilarious look at one of my favourite groups of organisms. I’m always pointing out lichens to groups I take into the woods here in Manitoba because they just so fun to explore. Most who come with me are skeptical at first, but I’m pleased to report there have been many converts by the end of the walk.